The Society for the Conservation of the Great Buddha at Shūrakuen (Shūrakuen Daibutsu)

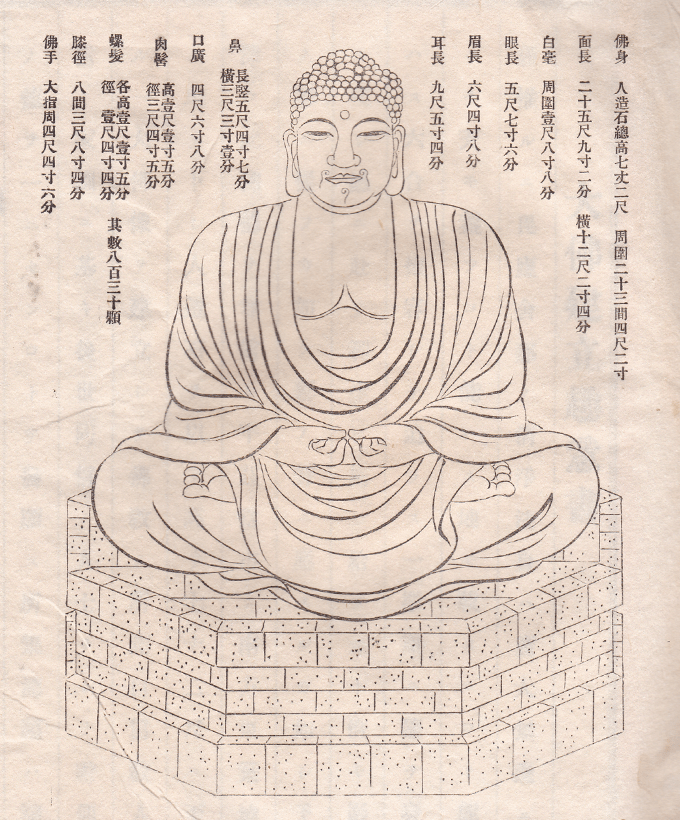

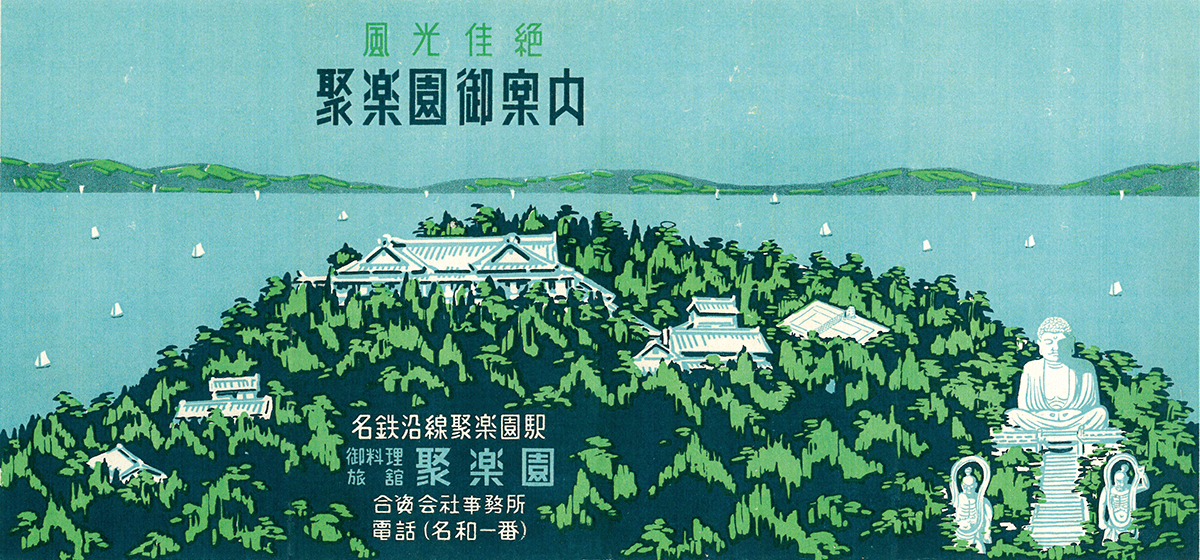

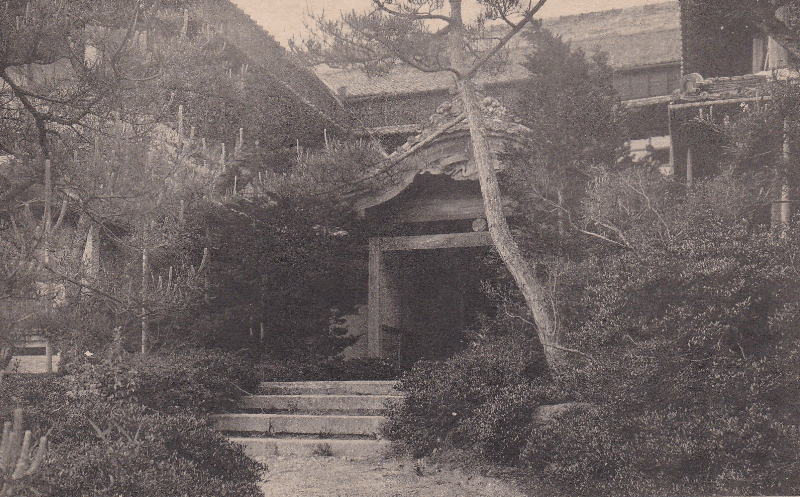

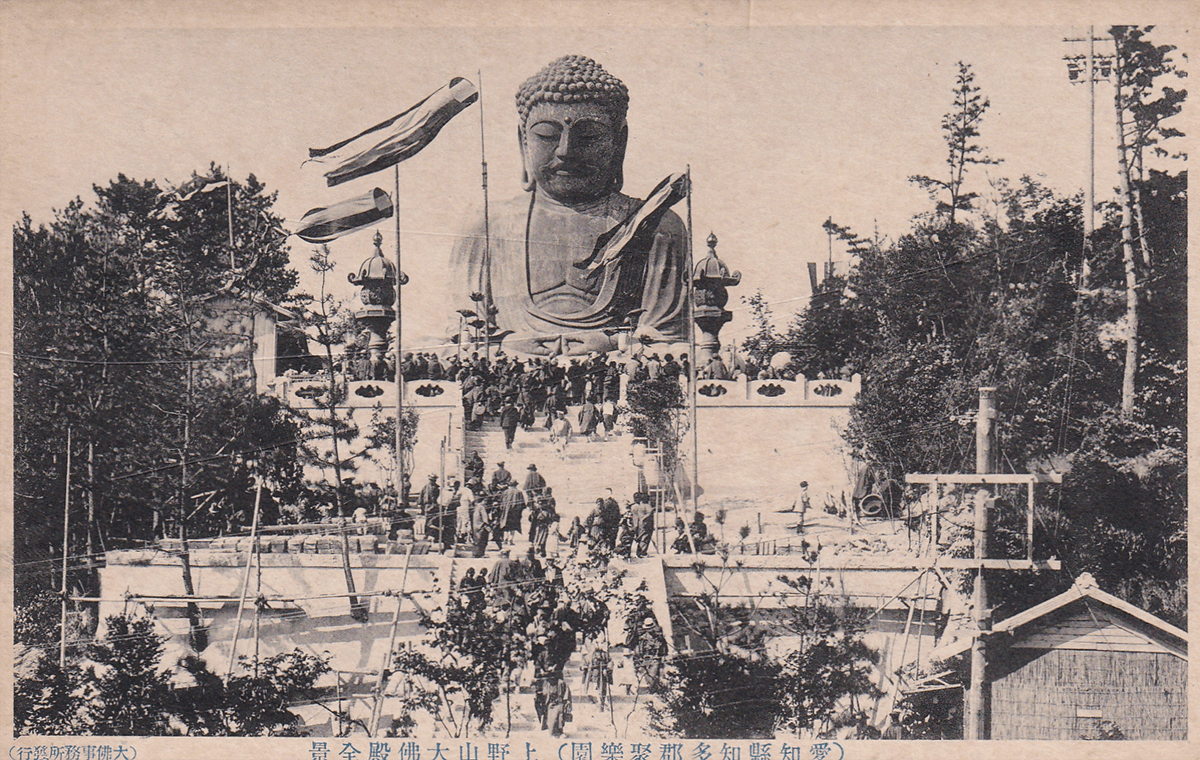

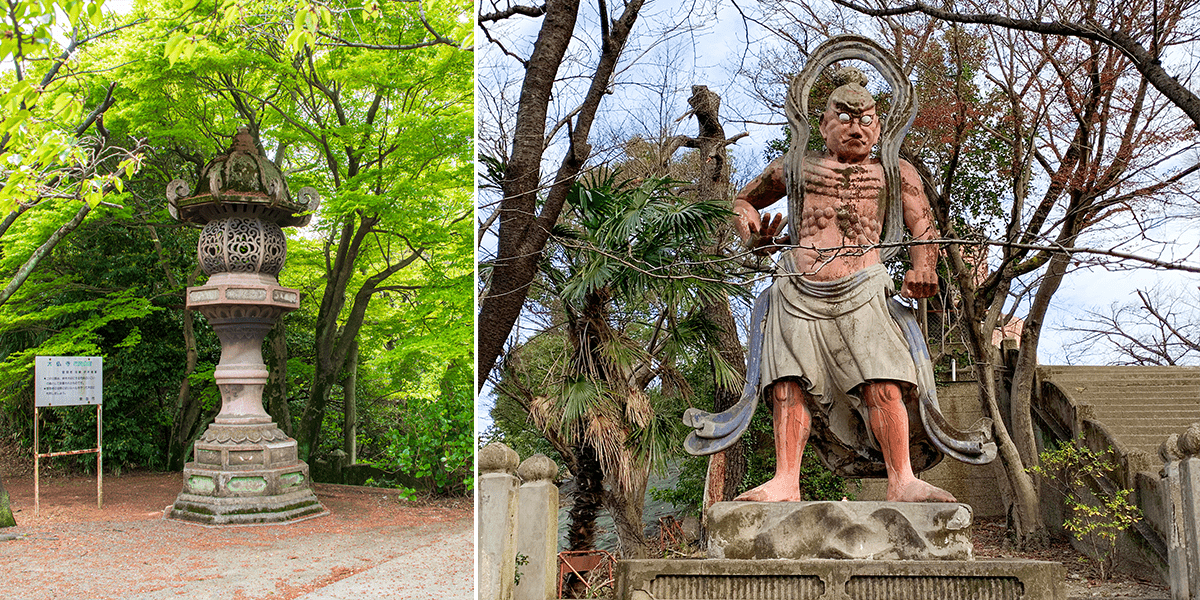

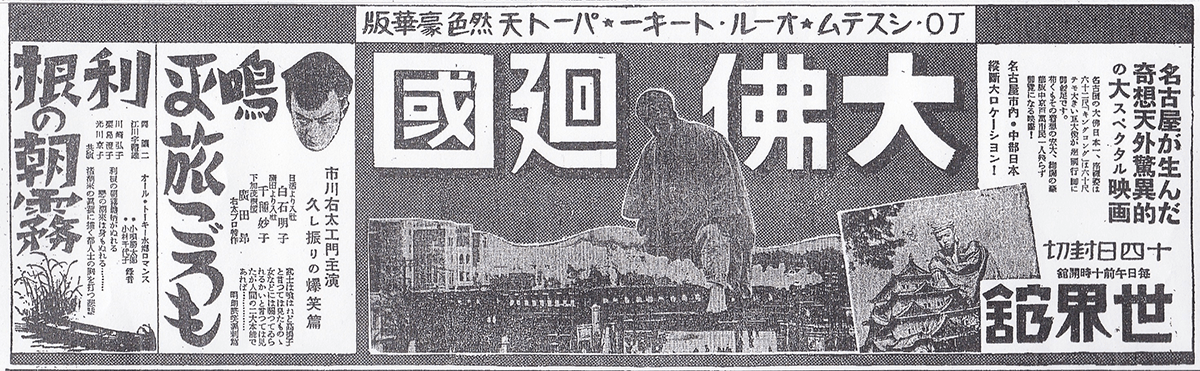

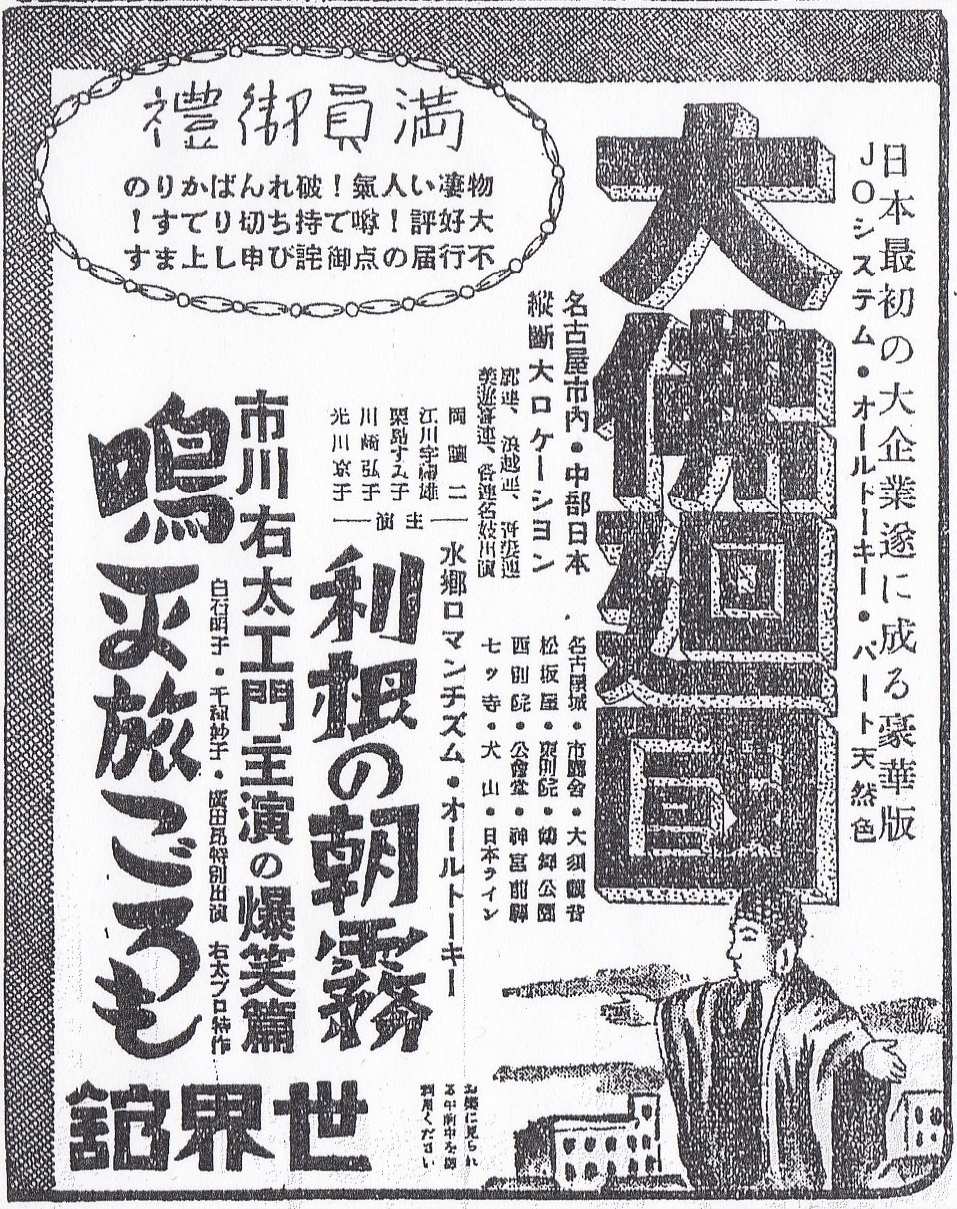

Our Society is a non-profit organization established with the chief aim to conserve the Great Buddha/Daibutsu (a Japanese term for a Buddha statue ‘great’ in size) at Shūrakuen municipal park, formally a traditional Japanese ryōri-ryokan (‘culinary inn’) complex, in Tōkai City, Aichi, Japan. The Daibutsu was consecrated in 1927; made from reinforced concrete with a height of 18.79m (without the plinth), it is commonly known as Shūrakuen Daibutsu. As the condition of the statue has deteriorated since its consecration, our Society, which is run by the descendants of the founder and other caretakers of the Daibutsu, has launched an initiative in its conservation efforts to pass it on to the next generations.

As part of the wider conservation of Shūrakuen Daibutsu, our secondary purposes are to protect its related historical and cultural heritage and to advance the research into it from the perspective of modern local history, in collaboration with individual supporters, the local and regional authorities, Buddhist organizations, academic institutions and private companies. Through these activities, we wish to contribute to the local community in a reciprocal manner and promote tourism centred around the Daibutsu.